Original Item: One-of-a-kind. Private Richard D. Yeagley from Lebanon, Pennsylvania served in World War Two as a member of the Anti-Tank Company, 271st Infantry Regiment, 69th Infantry Division. he is mentioned numerous times in "A History of the 271st Anti Tank Company - 69th Infantry Division" which can be downloaded at this . Included in this grouping are the following items:

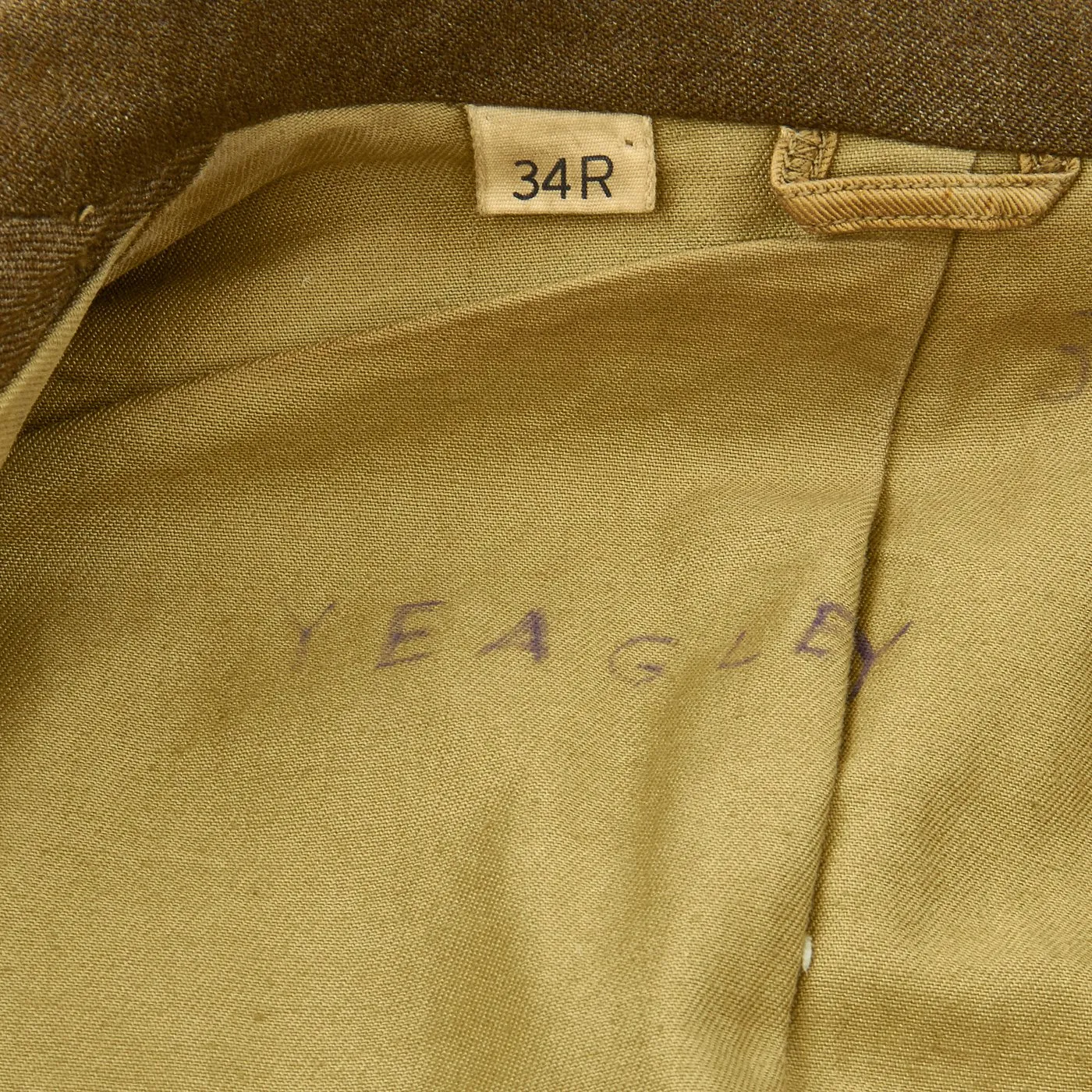

- WWII Ike jacket with dog tag chain border Seventh United States Army insignia patch to left shoulder, dog tag chain border 69th infantry division insignia patch to right shoulder, enamel distinctive unit insignia lapel pins, unique Combat Infantryman Sterling Badge with 69th ID enamel insignia to center. Medal ribbons: Army Good Conduct Medal, American Campaign Medal, World War Two Victory Medal, European-Africa-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with two campaign stars. Ruptured duck patch and 3 overseas service bars on left shelve for 18 months served overseas. Jacket is size 34R and named YEAGLEY in ink cross the interior lining by the neck.

- Research Binder with copies of Yeagley's original wartime documents as ell as additional research as well as his obituary and a printed copy of "The Story of Anti Tank Co. 271st Inf".

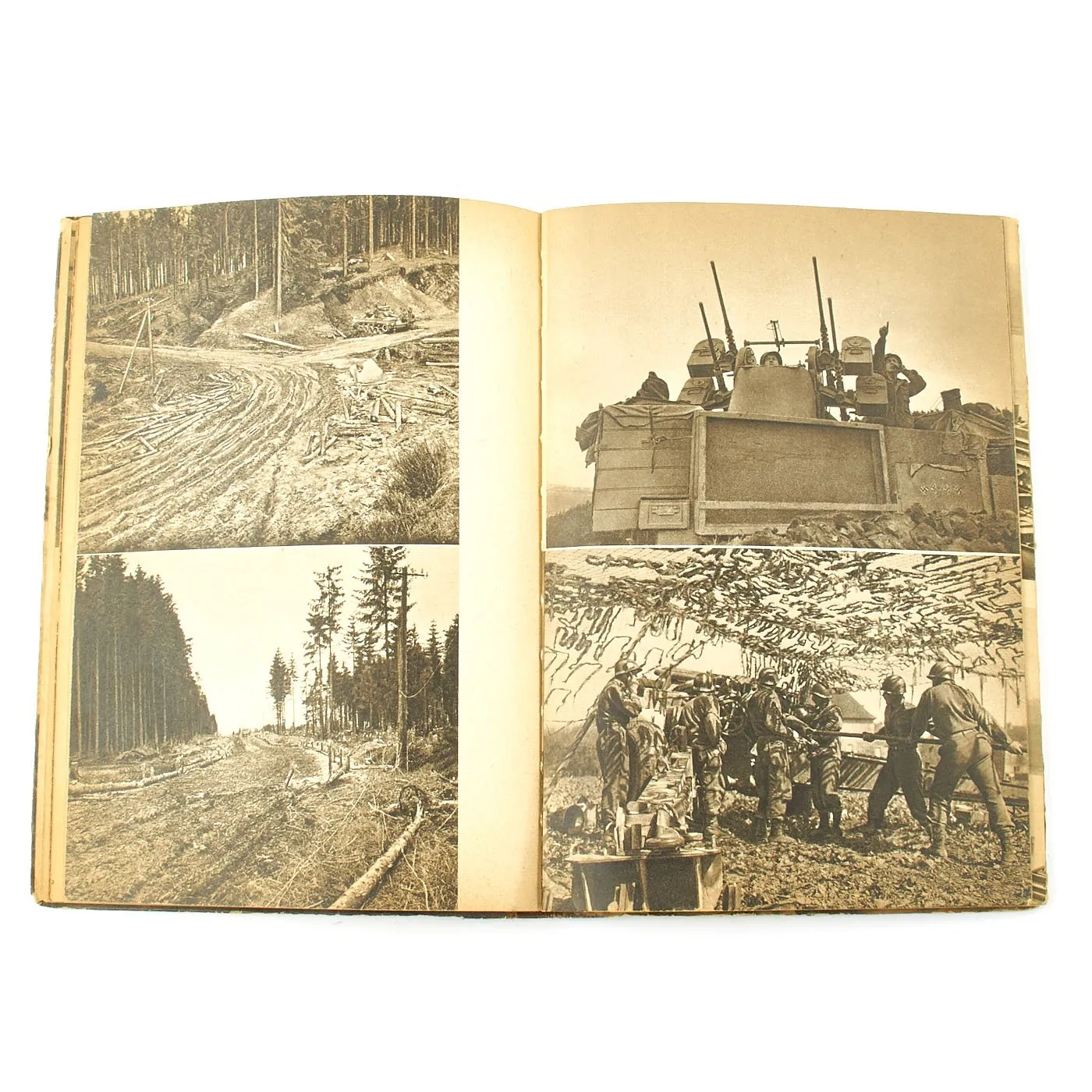

- Original copy of the 69th Infantry Division Pictorial History book.

Approximate Measurements of IKE jacket:

Collar to shoulder: 10.5"

Shoulder to sleeve: 26.5"

Shoulder to shoulder: 16"

Chest width: 19"

Waist width: 17"

Hip width: 24.5"

Front length: 16"

History of The 271st Infantry Regiment

On 15 May 1943, a new division, the 69th, was activated at Camp Shelby, Miss. One of its regiments, the 271st, was born the same day, and this is its story to date. Every soldier, no matter what his present desire, Army career or civilian life, will long remember the outfit with which he went to war. Perhaps these are some of the things that will come to your mind at the American Legion Convention many years hence, when someone asks you what outfit you were in.

Camp Shelby, Mississippi! Who will ever forget it? That place could get so cold in the winter and so hot in the summer! For over 17 months, we lived and trained there, among the woods and chiggers, in the dust and mud of good old DeSoto National Forest, until many began to think that all the world was Mississippi, and that Hattiesburg was the capital of the world. You could get a good steak in Hattiesburg for about three dollars and a quart of blood, and living space was adequate if you were lucky enough to have a trailer or a tent.

“The 69th will never leave Shelby!” Remember? That byword must have been put out by the Hattiesburg Chamber of Commerce to give its citizens some good excuse for living there! It reminds you of the man who kept saying to the end: “They can’t do this to me!”

It is a proven fact that no division in the Army got more or better training than we did. A great many of our officers and men have been with the outfit since it was activated. But who is there among us who can forget how we got that old B.B.B. nickname? It seemed that you’d just about be getting used to sleeping in a bunk, and your chigger bites would be healing a bit, when someone would announce that we were getting “garrison bound,” and off we’d go to the woods again. Oh well, in the light of later developments, we were grateful for the experience we’d had.

The time spent in Shelby netted us many lasting friendships and pleasant associations. Also not to be overlooked is the fact that the “Southerner” ran through Hattiesburg, and there was always New Orleans. Remember?

It was on 31 October 1944 that we crawled out from under a mountain of equipment and sank down in a Pullman chair for a last look at Camp Shelby. Reactions to the parting were mixed and varied. There were those who had been there so long that they would actually miss such landmarks as Lake Shelby, Highway 49, O.P. 5, Whiskey Creek, the red-scarred hill, and the “lone pine tree.” Some welcomed the move, as the start of a new adventure, the culmination of our extended training. There would be no more “D” Series, no more Biloxi Bounce, nor Hattiesburg bus lines. This was the point at which we were to start the long trek to a fighting front.

But where were we going? The Pullman porter knew, but like all railroad employees, he was the vaguest source of information, and there remained only the usual unimpeachable channels of latrine rumors. It wasn’t long, however, before word started spreading from car to car that we were doing the “Jersey Bounce!” The Yankees in the crowd started immediately to expound on the merits of New Jersey, with assurances to all who had never been there that they were now to see how the “other half” lived. It was true. We were on the way to Camp Kilmer, near New Brunswick, and the prospect was thrilling to those lucky individuals who happened to live in the vicinity. The trip was pleasant, with the usual troop train diversions. Some played cards, others sat and talked; some just sat. The food was good, and the Pullman bunks were clean and comfortable.

The first group of the regiment arrived at Kilmer early the morning of 2 November, and all during the day, the balance of the command arrived. To the accompaniment of some lively music, we marched to the two-story barracks that were to be our home for the next few days. Almost immediately began the overseas orientation schedule, and it was amazing to note the efficiency with which the many details were accomplished. Remember the cargo nets, the lifeboat drill, the lectures on censorship, the procedure in case of capture, the introduction to the Army’s new type of gas mask, etc.? Or who will forget that physical exam, where they passed you by an electric bulb, and if they couldn’t see through you, the seal of approval was put on your forehead, the equivalent of a free ticket for an ocean trip.

Of the many good features of Kilmer, its most appealing was its proximity to New York, just 20-odd miles away. Remember those passes to the big city? Time Square, the Village, the Music Hall, and the way you skidded through the gates in Penn. Station for that 5 a.m. train back to Kilmer…There was so much to do and so little time in which to do it…Take a last look; pour down that last scotch and soda…It may be a long time. It was even harder for those who had been able to get home and had to say the last farewell when the last pass neared its expiration hour. But this was what we had been training for.

On 14 November, we again boarded a train, but this time it was a very short trip; in fact so short that it almost wasn’t worthwhile to get out of the GI harness, since they were soon lining us up to get off. Next a ferry ride, but without the familiar atmosphere of the accordion player and considerably less comfortable. Across the river, amid much speculation as to where we were headed, we finally pulled in at Pier 44, where they added insult to injury by having a band play “Somebody Else Is Taking My Place.” The Red Cross was on hand to pass out coffee and sinkers to those who still had strength enough to hold up the cup. Beside us was a large ocean liner, dark and gray in the night. It was at this time that all who had the hot tip on the “Queen Mary” paid off their bets, and we all struggled up the gangplank of the MS John Ericcson. Formerly the Swedish luxury liner Kungsholm, she was to be our home for several days. The ship was spacious and well planned as a trooper, so that there was no confusion as the men were rapidly assigned to their quarters. A new and thrilling experience for most of us, and about this time, we began to wonder if the 69th would ever leave Shelby!

Once assigned and quickly oriented to the need of wearing lifejackets, we put the weary bones to bed on canvas cots, which were in four tiers and strung in every possible place. It was not until 0600 the next morning that we set sail, and in the gray mist of early morning, we saw the familiar and beloved skyline of New York drop from view. Through the Narrows, and out into open water, where we were soon joined by many other ships that were to be in our convoy. One had only to look around at these vessels to be impressed with the stupendous shipping problem that war presented and be struck with the efficiency with which the problem was being met.

Those of us who had been landlubbers all our life were soon tossing coins to decide which was port and which was starboard, and trying hard not to look too lost when someone said something about the “Liberty two points off the port bow.” It wasn’t long before the gulls began to drop back, and we came to realize that the ocean was a pretty large place.

Life aboard ship was fun, although the first few days, there were many subscribers to the idea that all the world should be land. Several green complexions and “I-don’t-care-if-I-die” expressions were noted about the third day out when we hit a rough sea. A lot of those fellows whom you saw bent over the rail were not looking for fish. And you remember how training was conducted for those hardy souls who were still able to sit up. In one corner you’d see a group dutifully listening to the voice that was telling them how much beer they could buy for a shilling, and if you stumbled further down the deck through the mass of humanity, it was common to see a bunch of puzzled faces and unwilling mouths trying to “parlez Francais” in a few not-so-easy lessons.

Then they had Ship’s Inspection each day. There were so many people in the inspecting party that it was hard to tell where today’s inspection ended and tomorrow’s began! You couldn’t stay on deck – they were cleaning it; you couldn’t go below – they were inspecting it; and the crew’s quarters were off limits. That left one alternative, namely jumping overboard. It’s a good thing we were following the southern route; it was easier to swim alongside the ship during an inspection.

This was our first opportunity to buy cigarettes for a nickel a pack, and maybe you think the men didn’t stock up. How many of us shed a sympathetic tear for the civilians at home who couldn’t buy them at any price. Special Service did a fine job on board ship, showing movies, putting on shows, arranging religious services, providing recreational facilities, and in general, making things as pleasant as possible for the men. The food was good, and on Thanksgiving Day, we were pleasantly surprised to find turkey and all the trimmings awaiting the lusty appetites that the salt air had given us. It was a memorable meal.

As for excitement during the trip, there wasn’t any, other than the thrill of standing on deck in the evening and watching the white phosphorus in the cleaved water alongside the ship, or feeling the tang of the sea air against your face. Almost made you understand the mariner’s devotion to the sea. One evening, a brightly lighted hospital ship passed near our convoy, and another time, several depth charges were dropped by the escorting naval vessels, shaking our ship considerably and making the men in the lower deck compartments wonder if their nickname, “Torpedo Junction,” might not be too far from the truth.

The 10th day out, gulls were sighted, and we knew that land could not be too far off. Our destination had already been announced, so that everyone was eager for his first glimpse of England. On the morning of 26 November, land was sighted, and we were soon passing the beautiful Isle of Wight, in southern England. From here on, it was impossible to keep the men from the rails, as no one wanted to miss a moment of it. Remember all those landing barges we saw as we approached Southampton? Could anyone help thinking of all the men who had recently used them to storm the citadel of AH’s Europe?

They say that England has two seasons, winter and August. We missed August. It was cold as we debarked at Southampton on 27 November to entrain for our billet area. After being served some very welcome coffee and doughnuts by the Red Cross, we helped each other get through the narrow doors of the railroad coaches, and were carried about 15 miles inland to Winchester, the ancient capital of England. Winchester, rich in story and legend, where the statue of King Alfred looks down the crooked, winding streets, and the solemn majesty of Winchester Cathedral stands quiet guard over the city, able to tell so many stories of the changes it has seen in man’s life.

Most of the regiment was billeted in Winchester Barracks, in the middle of the city, and here one got his first taste of British military tradition on noticing that over each door was inscribed the name of some famous battle in which the Hampshire Regiment had participated. After we cleaned up and got the chill out of the buildings, they turned out to be quite comfortable. The 3rd Battalion went to nearby Arlysford and there received their billets in its vicinity. Headquarters and I Company were at Armsworth House, Companies K and L were at Bighton, and M Company stayed at Bishop’s Sutton.

You will recall the many points of interest in and about Winchester. The Cathedral, built in 1079, the church of St. Cross, the Guildhall, King Arthur’s Roundtable, the Westgate, etc. It was an interesting and informative insight into British history and tradition. Remember too the pubs, the “alf & alf,” fish and chips, and last but not least those passes to London. Many lasting friendships were made in England during the seven weeks we stayed there. Much was done toward working out a more thorough understanding between Americans and Britons. Who could help but marvel at the courage and tenacity of these people upon seeing the havoc wrought in London and other cities by air raids and V-bombings?

On 16 December, we sewed our patched back on our sleeves and were permitted to tell people the identity of our unit. Christmas found us becoming quite British in our manner and having a party for those pink-cheeked English kids, most of them evacuees from bombed areas. Made you a bit homesick, didn’t it?

Also on Christmas day, we received a rush call to furnish riflemen as replacements for the forces in the Ardennes. Eight hundred and thirty-one men were sent to the front, which was saddening to those who remained behind while all this was going on across the Channel.

The holiday week found many companies having private parties in the large gymnasium at Winchester. Music and beer were plentiful, and the English ATS girls and WRENS helped so much to brighten the occasions. Many of our men were surprised to see how well these girls could jitterbug, and equally amazed at their ability to consume bitters.

New Years came and passed quickly. The pubs all closed at 2200 as usual, so that celebrations were in many cases nipped in the bud. Somehow or other, the raucous celebrations of former years would have seemed in bad taste before these people who had been bearing the burden of war for so long.

Training was conducted and numerous checks made of the combat serviceability of our equipment, which had been arriving in large piles. Weapons were zeroed in on the range, and as far as possible, we attempted to complete the finishing touches before going across the Channel. Behind the pleasant scenes at Winchester, there was ever present the sobering thought that soon we would be put to the test.

When the HMS Liangiby Castle left Southampton on 20 January, there were many who were already thinking about overseas stripes and rotational furloughs. This ship was a sister ship of the ill-fated Morro Castle and was very comfortable, having been completely refitted as a trooper. The Channel was safely negotiated, and at sunrise the morning of the 21st, we got our first glimpse of the snow-covered French coast. Since the sea was rough, we had to wait till late next evening before climbing aboard LCIs to go ashore. Who will forget the sensation he got when the nose of that LCI plopped itself down on the dark shore of LeHavre? Or that seemingly endless walk with full equipment through the ruins of the city to the railroad station, where those deluxe coaches awaited us. They were the famed 40-and-8s, and we were soon to learn why our fathers had always spoken of French boxcars as a bad memory. There had been little change since they rode them, except that the cars were 25 years older and more mellow with age. Designed to carry 40 men or 8 horses, it would appear from the odor that they had been concentrating on the latter, and from our later impressions, we all wished that they had been devoted exclusively to horses.

Snow fell all night, and it was bitter cold. We all lay huddled in a shivering mass of humanity, and no one got much sleep. Some humorist suggested setting each other’s clothes on fire, but the supply sergeants expressed a strong veto. Next morning, we saw why Normandy has always been pictured as a place of beauty. The snow had covered most of the scars of war, and the scenery was lovely. The hedgerows and the neatly laid-out farmland, with the fruit orchards in trim rows; it was easy to appreciate the fame of Normandy. Yes, it was beautiful, but God, it was cold!

At 1600 the next day, we arrived at our destination. The organic vehicles had gone ahead in motor convoy, carrying with them the quartering party, so that when we arrived, we were driven with a minimum of confusion to our billets. Schoolhouses, private homes, chateaux and other buildings had been picked for us. We stayed in what was left of a French chateau, since the Jerries had looted the place of everything worthwhile, even tearing out the wiring and fireplaces in their retreat. Regimental CP (Command Post) was at Buchy, and the battalions were spread out in neighboring towns.

With the aid of our GI French books and our high-school French, we soon learned that the French were warm and sincere in their greeting, and that they had suffered much. We also were introduced to two staple items of French life, apple cider and huge loaves of oven-baked bread. There was a spirit of amity and goodwill between us and the Normandy French.

Some training was carried on, but most of the time was devoted to servicing weapons and equipment. We were preparing ourselves mentally and physically for what lay ahead.

On 1 February 1945, we left Buchy enroute to a Marshalling Area. It was Liesse-Gizy, or “Lizzie Gizzie” as it became known, and the regimental CP was set up in the nearby town of Pierrepont. The mud here was so deep that Retreat ceremony had to be cut short, since the men would disappear from sight in a few minutes! You had to take three steps before your shoes could move. However, we were fortunate enough to secure large tents, which were easy to keep warm, and cots upon which to sleep. The place will be remembered by most of us as “Tent City.” People were beginning to wonder if the 69th would ever leave Shelby.

We were getting to be seasoned travelers by this time, so it was with little strain that we packed up and took another train trip on 7 February. After another blissful 24 hours in the boxcars, we detrained at Pepinster, Belgium, and were put aboard trucks. Just as we started, so did the rain, and a miserable few hours were spent in the trucks, cold and very wet. As always, the motors had gone on ahead in motor convoy, and by the grace of someone’s clever planning, we all ended up in the same place, namely the town of Waimes in Belgium. Here again, we saw evidences of the destructive force of war, as the place had been heavily bombed. In spite of what they had suffered in the war, the Belgian people were warmly hospitable. Although our stay was a short one, there were many evidences of goodwill, and even appreciation for their having been freed from German domination.

Entering Germany

The 10th of February was the day we entered Germany. That morning, we moved out, combat-loaded, and took up the positions occupied by the 395th Infantry of the 99th Division in the vicinity of Hollerath, just inside the first belt of pillboxes of the infamous Siegfried Line. By 1630, all positions had been taken over, and the battle-green 69th was ready to apply the principles learned in all the months of training.

The men were far from comfortable that first night. With only one blanket and a sleeping bag in the below-freezing weather, not to mention the fact that we were subjected to harassing artillery fire, supplemented by “screaming Meemies” and considerable use of the flares. Extensive patrol activity, aimed at feeling out the strength and disposition of the enemy, was carried out for the following two weeks, and it was not long before most men had become quite used to life at the front. As someone put it: “You don’t have to worry about the ones you can hear!” After a time, you can fairly accurately tell where they will land. Morale of the command was excellent, especially when the kitchens arrived in the area, and it was possible to send up hot food to the men in the line.

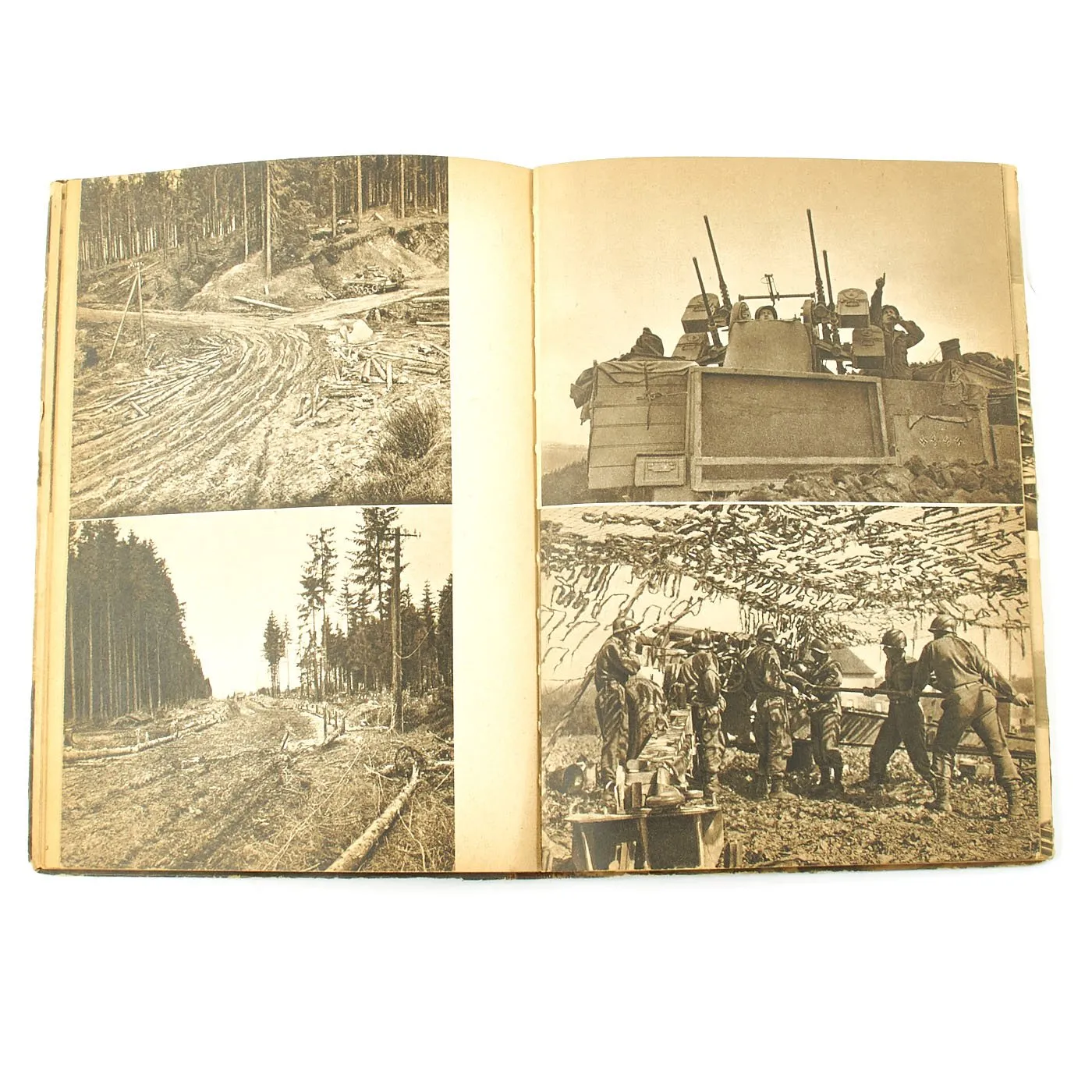

During this period, all duffle bags were turned in, so that the units could travel fast and light. Condition of roads in the area was wretched, which seriously accentuated the supply problem. In the 17 days before our first attack, 30 prisoners were taken, of whom 10 were captured by our patrols. In this area too, great emphasis was put on maintaining weapons and equipment as well as much attention to proper sanitation.

First Attack

After being postponed several times, our first attack was launched at 0600, 27 February. We arose at 0300, had breakfast and spent the remainder of the time in final preparations. The night was very still, and a slight mist hung in the air, an ideal morning for our purpose. It is not boasting to say here that anyone who had come into our area that morning could have accurately predicted that we would measure up to any combat assignment given us. There was no visible nervousness, no confusion, no slackening of morale. Everyone stood ready to perform his assigned tasks as though it were maneuvers at Shelby, secure in the knowledge that whatever exigencies arose, we were ready. To borrow the much-used expression: “This was it!,” and every man in the 271st knew it.

The plan of attack was as follows: The 69th Division, two regiments abreast, with 661st Tank Destroyer Battalion, were to seize and hold the high ground between Honningen and Giescheld inclusive, in order to clear the Hellenthal-Hollerath road for use as a supply route.

The 271st Infantry, with 879 Field Artillery, 880 Field Artillery and Company A of the 269th Engineers in support, would seize and hold its portion of the Division objective, after which it would be prepared to assist by fire the 273rd in the capture of Giescheid. The Second Battalion, with 879 Field Artillery, a platoon of Engineers, a platoon of Company C, 661 Tank Destroyer in support, was on the left; the First Battalion on the right, and the Third Battalion in reserve. The Third was to stand ready to furnish carrying parties to the attacking battalions during the hours of darkness, and also to occupy Dickerscheid with one company, upon call from Second Battalion, when the town was captured.

Cannon Company supported the attack of the regiment, with priority of fire to the Second Battalion. Anti-Tank Company was to provide litter squads, and also have its mine platoon sweep the roads to Dickerscheid and Buschem, after clearing mines in the vicinity of the bridge site. Company A of 269 Engineers was to construct a bridge in Second Battalion sector, and also clear mines and abatis in the First Battalion area. These were the plans, and with them well in mind, the 271st Infantry Regiment went into action the morning of 27 February 1945.

The First and Second Battalions crossed the line of departure on time and advanced towards their objectives. With a few unavoidable exceptions, the regiment reached and held its objective according to plan.

The First Battalion, in the face of stiff resistance, achieved its objective by 1030, with all companies committed. The remainder of the day they spent digging in and consolidating their positions.

Company G of the Second Battalion attacked Dickerscheid and by noon had taken four houses; by 1700 had nearly completed mopping up the town. Company F, attacking Buschem and Honningen, was able to take half of Buschem before being pinned down by fire from nearby Honningen, and was ordered to hold its present position for the night. One platoon of Company E assisted G in mopping up Dickerscheid and clearing the woods east of the town. Company K was then ordered to occupy Dickerscheid, which was accomplished, releasing G Company to close the gap between themselves and F Company.

The Third Battalion was alerted that night, but not committed until next day. Next morning, E Company was committed to assist F Company, and the two companies cleared Buschem and went on to take Honningen. Two counterattacks were repulsed in the area.

At 1400, 28 February, Company B led the First Battalion in its attack on Hahnenberg, moving towards the village from the draw southwest of it. Concurrently, plans were made for the Third Battalion, Company I on the right, Company L on the left, to take Oberreifferscheid, following a five-minute artillery preparation. Company L, however, experienced some delay in the assembly area, and did not cross the line of departure until 1450. Nonetheless, the attack was successful, and positions were consolidated.

In all the advances of these two days, enemy artillery, mortar, nebelwerfer, and machine-gun fire were encountered. However, our artillery countered with good results, causing the enemy artillery to cease firing temporarily.

Throughout the attack, morale remained at its high level. Everyone performed his duties, and many far exceeded the call of duty. It was not a pleasant experience, but through close cooperation and teamwork, all missions were accomplished, and each man emerged more mature, wiser, more aware of the task ahead.

Praise must be given the Medical Detachment of the Regiment. Anyone who heard the cry, “Hey, Medic!,” in the heat of battle, will never forget the manner in which that call was answered. With disregard for personal safety, and themselves suffering casualties, our Medics were outstanding in the performance of their duties. Instances of aid men continuing their ministrations under sniper and mortar fire were common. There is no greater aid to morale than the knowledge to the individual that, if he is hit, there is help close behind. Evacuation of casualties was done expeditiously, to which fact many men today owe their lives.

One hundred and seventy prisoners were taken in those two days, most of them by Company G in the Dickerscheid area. Twenty-four machine guns were destroyed, two captured, eight 80-mm mortars and six 50-mm mortars, and one 7.5 Infantry howitzer were destroyed; one anti-tank gun, four 88-mm self-propelled guns were knocked out and one battery of enemy artillery was silenced.

Casualties in the regiment were reasonably light. One officer and 38 men were killed; one man died of wounds, 19 were seriously wounded. Three officers and 117 men were missing in action, and non-battle casualties included four officers and 107 men. Total casualties for the period were nine officers and 305 enlisted men.

The first day of March found the regiment still advancing. Having captured the village of Wahld shortly before midnight on the 28th, Company B went on to occupy Hescheld. Company C sent a platoon to B as reinforcements, while Company A adjusted its positions to tie up with B. Other company positions in the regiment remained the same; lines were adjusted and straightened, positions consolidated and contact established. Anti-tank weapons were moved well forward and roads were swept of mines. A bridge was erected to provide a continuous road to the First Battalion. Companies G and K changed places, restoring tactical unity to both battalions.

During the first few days of March, our entire front was under sniper and artillery fire. In Buschem, the anti-tank guns had to be moved to new positions after coming under direct fire of 88s. Most of the companies were able to get hot food to their men and to issue them clean, dry clothes, something which had not been seen for many days.

There were several minor skirmishes, which it is believed were aimed at forcing us to disclose the location of our weapons. Occasionally, there were barrages of artillery and mortars, most of which fell in the Third Battalion area. Small-arms fire was limited.

Schmidtheim

German prisoners taken the morning of 6 March confirmed the fact that the enemy was leaving his positions and pulling back. The obvious reason was the large-scale offensives being launched on both our flanks by the bulk of the First and Third Armies who were close to effecting a function just short of the Rhine. The Krauts were fast deciding that the best way for them to travel was east and fast!

Accordingly, when a large-scale reconnaissance disclosed an almost complete lack of potential resistance in our sector, a plan was formulated whereby we could make a big move to the vicinity of Schmidtheim. This was the plan: At 0800, one reinforced company of the First Battalion would push out on reconnaissance in force to seize and hold the town of Schmidtheim. The remainder of the battalion would move on regimental order to occupy Schmidtheim, clearing up any pockets of resistance in its sector. The Second Battalion was to sweep the area in its sector of the regimental zone and leave a guard of not more than one squad in each town until relieved by the Military Government. Upon regimental order, the battalion would move to Schmidtheim. The Third Battalion was to seize the town of Hecken at dawn, and send one reinforced company to conduct reconnaissance in force and to outpost the regimental sector to the north and east of Schmidtheim. Special units were to support the advance as in previous similar movements.

The advance was made swiftly and almost without event. It was apparent that the enemy was withdrawing faster than our troops could keep up with them.

First Battalion arrived in Schmidtheim at 1330 and then moved on to clear the area to the east at 1715. The Second Battalion completed its mission, clearing the pillboxes in the regimental area. Third Battalion moved out at 0900 and after reaching Schmidtheim, Companies K and L went on to the east at 1500. Four towns and 14 prisoners were taken in this move. When the area east of Schmidtheim was cleared, the regimental Command Post was set up in Blankenheim. Regimental Headquarters Company and Anti-Tank Company set up in Blankenheim, as did the entire Second Battalion. The First and Third Battalions were in Schmidtheim. We learned at this time that we had been pinched out by the junction of the First and Third Armies and must await further developments before being recommitted.

Blankenheim had been dealt heavy blows by our Air Corps, but our stay there was comfortable and gave the men a chance for needed rest, reorganization and servicing of equipment. It was brightened somewhat by the fact that some of our exploring non-coms were able to find and liberate a good supply of wine. A few lucky individuals were able to get passes to Paris. We remained in the Schmidtheim-Blankenheim area for 15 days, during which Special Service provided entertainment, and presentations of awards for heroic achievement and meritorious service were made. Shower facilities were set up, and clean clothes issued.

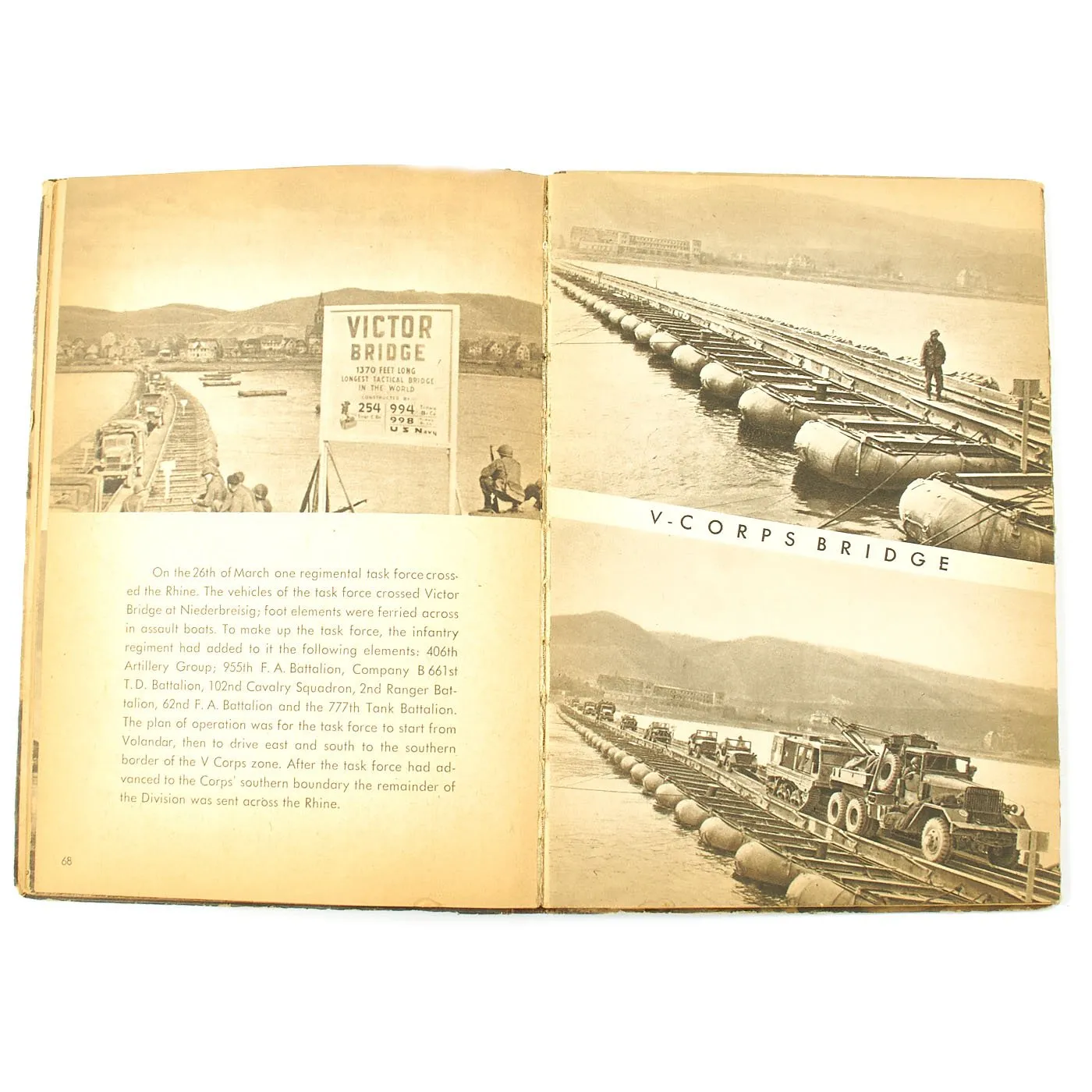

Our next movement was to an area which had been recently figuring large in the conduct of the war. On the morning of 23 March, we moved out in motor convoy, and after an uneventful trip, arrived at Sinzig, which had, in better times, been a resort town on the Rhine, but which was now the scene of more activity than any sector since the St. Lo breakthrough. Streams of men and equipment were pouring through to cross the Rhine in the area of Remagen. Here we saw the

Cart(

Cart(